The so-called Complexity Science has been around for a few decades now. Chaos, as well as complexity, were buzzwords in the 1980s, pretty much like Artificial Intelligence is today. There are Complexity Institutes in many countries. They speak of Complexity Theory. In a beautiful and recent video called “The End of Science”, Sabine Hossenfelder, speaks of Complexity Science and how it has not even produced a definition of complexity, not to mention a metric thereof. She also goes on to say that when Complexity Science will have the necessary math, which apparently hasn’t been developed yet, we can expect many breakthroughs in science. She finally says that:

“the biggest gap in science today is precisely the lack of a proper definition of complexity”

A statement she makes explains why we think that Complexity Science, in its present form, is dead: “we don’t understand the circumstances under which complexity arises”. This is, in fact, the original sin of contemporary “complexity theory” – it is seen as a process, as emergence thanks to self-organisation, as spontaneous combination of adaptive systems to spawn the so-called – yes, you guessed it – “complex systems”. It is thanks to the fact that complexity is seen as a process, and not as an attribute of things, like mass, momentum, or energy, that Complexity science has cornered itself into a situation out of which it has no way out. It will die. It is already dead.

A few remarks are in order here. First of all, Nature doesn’t distinguish between linear or nonlinear systems, complex systems or ones that are simple. It doesn’t care about chaos or man-made systems, or ones that she herself made. Nature applies the same laws of physics to everything, regardless to what it is and who made it. Therefore, inventing the term “complex systems” is just a matter of semantics, a matter of “accounting”. People like to categorize things and put them in (hermetic) silos. Many scientists like to do that. Science, however, has made great strides when it was able to generalize. It is in fact the goal of science to come up with laws that are universally valid, not confined to a particular corner of the Universe.

Our approach is to see

complexity as an attribute of a system, not as a process of its emergence

Most, if not all systems in the Universe, are the result of self-organisation. This would mean that the Universe is made up only of complex systems! Drops of water self-organise to form waves. Stars organise to form galaxies, amino acids organise to form proteins. Trees form forests. Individuals organise into societies. Planets organise to form solar systems. All these things happen thanks to the already existing laws of physics, which are complete and consistent (unlike the laws of mathematics, as Goedel has shown). This is why we think the idea of a “complex system” is unnecessary. Once you accept the idea of complexity as an attribute, it becomes obvious that there are systems that have little complexity and some that have a lot. Just like there exist systems with a small mass, or systems that possess huge energy. This is why laws of dynamics of Newton are applicable to tiny particles as well as to planets and stars.

Secondly, let us examine briefly the concept of theory. A definition of theory is “A set of statements or principles devised to explain a group of facts or phenomena, especially one that has been repeatedly tested or is widely accepted and can be used to make predictions about natural phenomena.” A theory can be verified in a laboratory. If it cannot, it collapses and vanishes and a new one needs to be formulated. Usually, a theory is built around a theorem or two, or it has a characteristic constant, or some equation, etc. Think of the gravity constant, G, the Planck constant h, or the speed of light, c. We can immediately relate these constants to their corresponding theories. But what about the contemporary complexity theory? Does it have a constant of some sort, a theorem that we could mention, an equation? Can it be tested in a lab? What would you test? The bottom line is: if you don’t have a theorem, an equation, a theorem or an experiment of some sort, you don’t have a theory. You cannot put together a bunch of romantic statements and call that a theory. Most importantly, if you claim you have a theory of “X”, you should be able to define what “X” is and how to measure it. A good definition of something centric to a theory thereof, should hint a way of measuring it.

This brings us to the current “definition” of complexity. Wikipedia proposes this: “A complex system is a system composed of many components which may interact with each other.” Such a definition is utterly useless, not to say infantile. It further goes to say that in a complex system, the interaction between components leads to collective behaviour, which cannot be inferred from the study of one such component. Again, you obviously cannot imagine that drops of water would form waves by just studying drops of water. The same may be said of man-made systems. Can you extrapolate what a car will do by studying its components? Of course not. Basically, these statements of the obvious cannot be called definitions because they don’t define anything. They certainly fail to offer any means of measuring complexity. And as Sabine Hossenfelder claims, it is all about the growth of complexity. But if you can’t measure it, your theory goes out the window.

Ontonix has devised a metric of complexity nearly twenty years ago. But let’s start with the definition of complexity:

Complexity is the amount of information in a system that results from the interaction of its components

Formally, complexity may be defined as C=f(S; I), where S stands for Structure and I is information, while f is a spectral norm operator. Since information is measured via Shannon’s Entropy, the equation may be rewritten as C=f(S; E). But entropy is also a measure of disorder. This means that C=f(S; E) combines the two most important trends and actors in Nature: the trend to create structure and the trend to destroy it, leading to disorder. Structure in this equation represents the exchange and flow of information between the components of a given system and may be pictured as a network or a graph. Typically, graphs and networks are described via their adjacency matrices. The entropy in this equation is not to be confused with the thermodynamic entropy (dQ/T). Since Shannon’s entropy is measured in bits, the units of complexity are also bits. The bottom line is that

this metric of complexity establishes a link between Physics and Information Theory

The C=f(S; E) formulation has enabled us to formulate a series of complexity theorems but it also possesses a very interesting property. Like all physical quantities, it is bounded. The upper bound is called critical complexity, and it quantifies the maximum amount of complexity (information emanating from structure) that a given system can hold before it collapses (its structure dissolves). It must also be stressed that complexity is not a static property of a system. It changes over time as a system evolves and provides new insights into its dynamics. That, however, is a matter for another article.

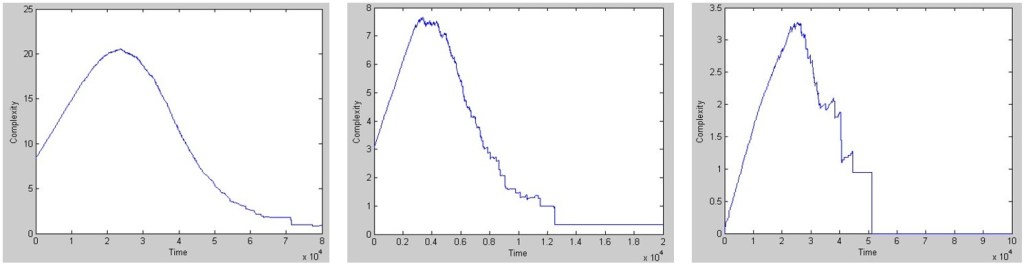

Our complexity metric has been applied to a myriad of systems over the years, ranging from stock markets and corporations, to hospitalized patients or proteins, or industrial processes and engineered products. It explains how a system needs a minimum, initial amount of complexity to survive and grow, how it evolves, attaining a maximum complexity level, and then decays, more or less gracefully, towards a certain “death”. The figure below shows the evolution of complexity of three systems. The one on the left grows and ages smoothly without incidents, while the one on the right undergoes a traumatic collapse. A loss of complexity implies a loss of functionality (and vice versa). If this is due to the failure of a critical component, this loss is faster and more pronounced.

So, why is contemporary complexity science dead, or on a course to certain death? Why is it that it hasn’t been able to even define complexity and, consequently, unable to provide a measure thereof? The answer has already been anticipated: seeing complexity as a process of self-organisation and emergence, and not as a property of systems, will not lead anywhere.

We know that real science starts when you begin to measure. What complexity science needs is, paradoxically, more science and less opinions. Numbers, not sensations. If, for forty years, one is unable to define the central concept of a theory, either the concept is flawed or he needs to change his theory.

0 comments on “Complexity Science is Dead.”